Wikipedia Sitemap |

|

|  Useful Links 1 Useful Links 2 |

It did not take long for word to get around that we were going to Canada. Everybody knew everything about everybody else. The house we could not sell because of government involvement, so we rented it out for the next 10 or more years. The 1946 FORD we sold to a fuel and coal business. Our bikes and 1923 Harley we sold, and we disposed of the rest of the stuff we couldn't take with us. We built a big wooden crate and stuffed as much as possible in it because we could each only take $100.00 cash.

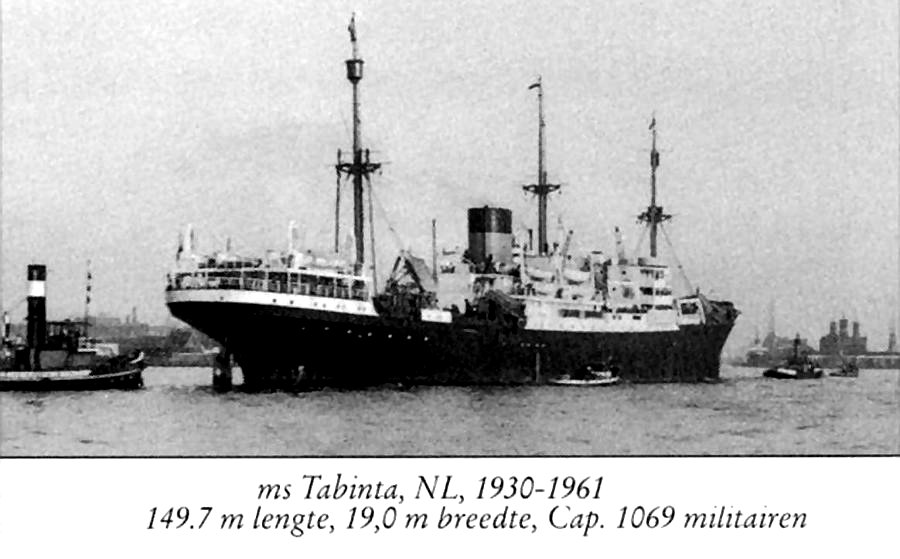

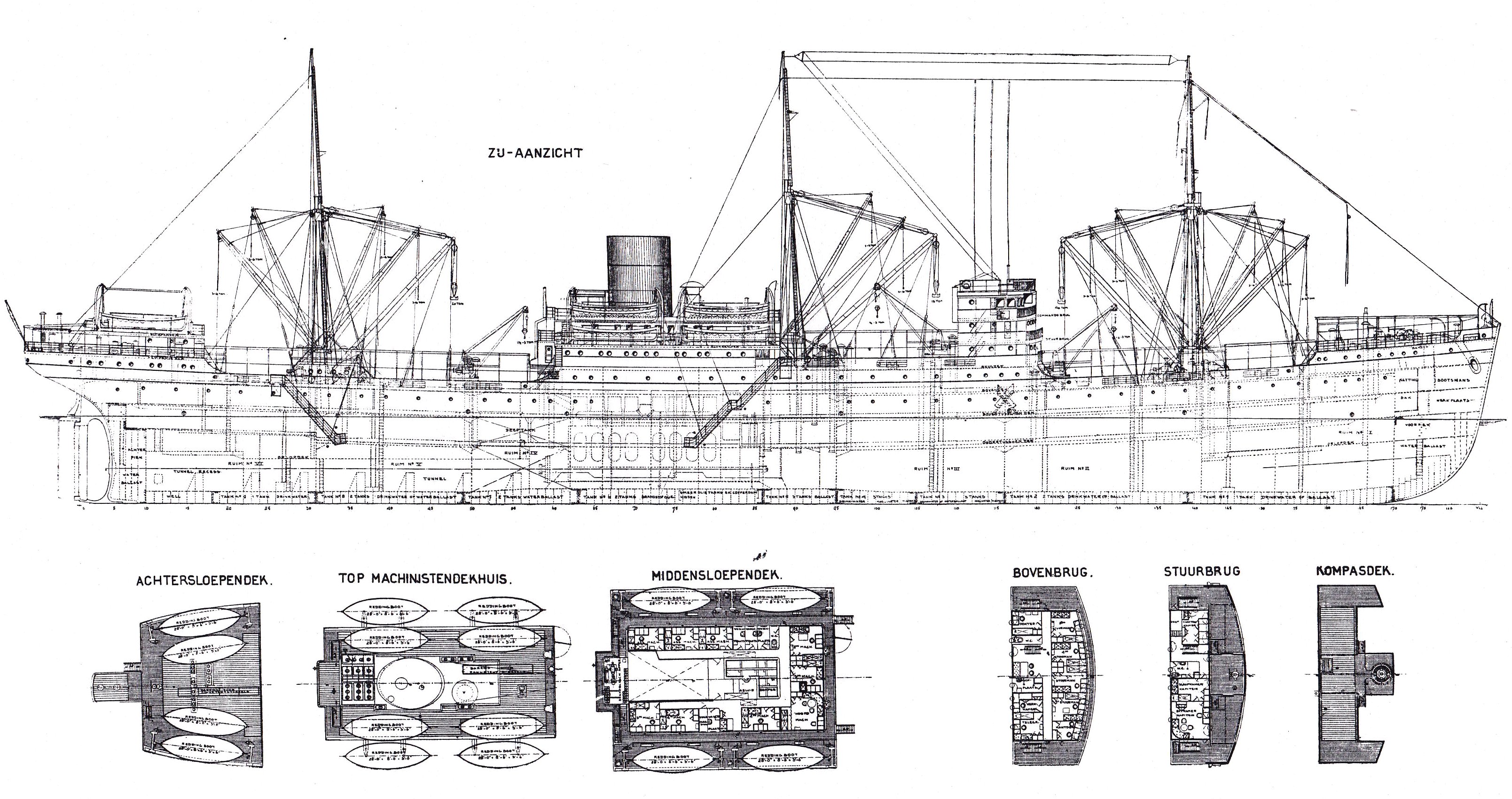

In Rotterdam, we boarded the MS TABINTA, an old Dutch East India freighter refurbished to a troop transport during the war, now it moved immigrants.

Our first trip on an ocean going vessel, with about 800 other passengers. Not all were immigrants, some were seamen going to New York to pick up a ship. Also there was a group of students going on a trip to the new world. The first day that we were out at sea, all was fine. In the afternoon, we saw the southern tip of England after leaving Hook of Holland behind us. We looked back and could see our Fatherland slowly sinking into the North Sea and finally disappearing. Would we ever again see the land where I spent the first twenty-seven years of my life?

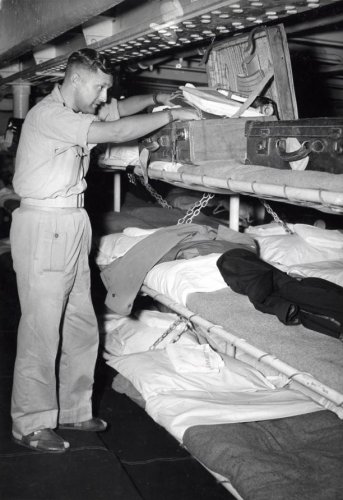

It was not much of a honeymoon trip so far. The men had to sleep in the front and aft of the ship, and the women in the middle where they got a better ride, I guess. It did not do much good because just as many women as men got seasick.The dining area held about two hundred so we had to eat when our number was called. It took approximately one and a half hours to feed these land lubbers. However that was only the first couple of days. It went faster, and faster, until they called all four sectors at once. Those that got seasick did not care to eat any more. They threw up all over the place, but mostly over the railing. One girl who was with the student group was the only one who still came with her plate to receive her vittles. I thought, my, she was a tough one. We had to go in line to the kitchen to get our portions. I was right behind her and when the little Javanese put the food on her plate, instead of saying "Thank you" she unloaded the whole contents of her stomach over the plate, the Javanese and the floor. Very appetizing, no?

Margaret did very well, much better than most. There was only one day when she felt so rotten she did not eat. I was one of the lucky ones for sure. I never had to throw up and never missed a meal.

We had some big swells and waves. I liked standing on the bow of the ship and looking down at the red painted water line. It was much different than I had envisioned an ocean trip. The waves did not seem to influence the movement. Movement was caused by the normous big swells. The water line came out above the water, in my estimation, six meters, then it went six metres below the line.

I asked a seaman what kind of weather we had. He said, "Rough seas today." I was not surprised because when the bow went down, the waves slapped over the deck behind me and smashed into the wheel house, time and time again, a wonderful sight to see. Only when the ship came up could I move from the bow.

For six days, we were in the open sea. When I stood in front, I let my mind wander and wondered what the early explorers must have felt, day after day farther away from home to an unknown land which might not even exist. The smell of the sea and the feel of the breeze made you wonder: were we in some different kind of world made only of water? Was there really a big continent somewhere over the horizon? One felt so little and insignificant in this enormous expanse of water and sky.

We finally entered the St. Lawrence Seaway. Man, this was a big river. We could see one coast but not the other for a long time. Every day it was posted how far we had travelled in 24 hours. It was mostly around 300 to 350 miles. Was that in nautical miles?

Related Resources:

Dutch emigrants to Canada aboard the MS Tabinta writing Detail Identifiable Information |  A Dutch immigrant to Canada aboard the MS Tabinta |  Homemade Wooden Crate of Dutch Immigrant |

Nautical mile from Wikipedia. "The nautical mile (symbol M, NM or nmi) is a unit of length that is approximately one minute of arc measured along any meridian. By international agreement it has been set at 1,852 metres exactly (about 6,076 feet)." Conversion: 1852 Meters (m) = 1.15078 Miles (mi)

Dutch Immigration Through Pier 21 by Carrie-Ann Smith. "Dutch immigration to Canada peaked in the late 1940's and 1950's. A poll taken in 1948 indicated that nearly one third of the Dutch population was prepared to leave the Netherlands for a better life elsewhere. There were two main factors; growing population pressures, and an economy which lay in ruin. Prior to WWII the Dutch government had not been in favour of emigration but it began promoting the idea in the post war years as one means of solving the overpopulation problem and their economic difficulties.

Many arrival accounts mention that Canada's popularity grew as more and more Dutch immigrants sent favourable reports of Canada back to their friends and relatives. These range from realistic accounts to tales of streets paved with gold. The bulk of the Dutch came to farm and Canada had plenty of room for that. Many young couples and families were sponsored by Canadian farmers and would work for the farmer for a year or two before buying their own land. The most popular program to aid Dutch immigration was the "Netherlands Farm-Families Movement" or the "Netherlands-Canada Settlement Scheme". The experiences of Dutch newcomers ranged from being housed in a chicken coop by an abusive farmer to becoming part of a loving Canadian family. It was the luck of the draw but countless brave Dutch immigrants were willing to risk it in order to get to Canada."

Netherlands Emigration and Immigration. "Emigration from the Netherlands: 1940 to 1970. Thousands of people left after World War II and settled in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the United States ... The Dutch emigrated for several reasons:

● Hunger

● Suppression by religious and government leaders

● The search for new land

● Emigration agents' glowing accounts

● Letters of encouragement from relatives and friends who had gone before.

Emigrants from the Netherlands left records documenting their migration in the country they left as well as in the country they moved to.